In 1964 Thomas Berger published Little Big Man. Filmed later as an anti-war parody by director Arthur Penn, the satirical novel recounts the exploits of 111-year-old Jack Crabb, as he wanders through the history of nineteenth-century western America. Along the way his life intersects with the likes of Wild Bill Hickok, Wyatt Earp, Buffalo Bill, and Custer. Through it all he has a front row seat to the so-called “winning of the West”— and he doesn’t like what he sees.

In 1964 Thomas Berger published Little Big Man. Filmed later as an anti-war parody by director Arthur Penn, the satirical novel recounts the exploits of 111-year-old Jack Crabb, as he wanders through the history of nineteenth-century western America. Along the way his life intersects with the likes of Wild Bill Hickok, Wyatt Earp, Buffalo Bill, and Custer. Through it all he has a front row seat to the so-called “winning of the West”— and he doesn’t like what he sees.

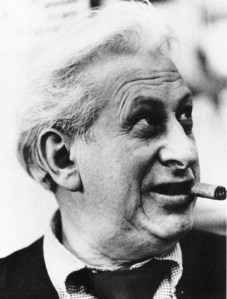

Crabb was a fictional character but each era seems to have its real life Jack Crabbs– people whose long lives spanned critical historical events, and whose actions, usually associated with their work, influenced events behind the scenes. One such real life character is John G. Morris (1916 – ). Quietly Morris became a key figure in the story of the 20th-century through his photo editing. He was on the scene in downtown Los Angeles early in 1942 to photograph the first wave of Japanese men, women and children being packed off to internment camps in the high desert. He then went to London as Life magazine’s lead photo editor in Europe during World War II and was in charge of coordinating the visual coverage of the Western Front. It was Morris who managed to save a handful of historic images shot by Robert Capa at D-Day when it was feared the entire set had been lost when damaged in development. Morris went to Normandy himself shortly after the invasion and snapped some memorable photos of his own. After the war, while at Ladies Home Journal, Morris published Women and Children of the Soviet Union with photos taken by Robert Capa. The photos provided Americans with a rare glimpse behind the Iron Curtain at the onset of the Cold War.

His career spans tenures with Life magazine, the Magnum photo agency, Ladies’ Home Journal, The Washington Post, The New York Times, and the National Geographic magazine. He knew and worked with the most celebrated war chroniclers of the times– Robert Capa, Henri Cartier-Bresson, W. Eugene Smith, Ernest Hemingway and David Duncan to name just a few. While he was the photo editor for The New York Times during the Vietnam War, Morris put Nick Ut’s “Napalm Girl” and Eddie Adams’ Saigon execution and John Filo’s student crying at Kent State on the front page — photos that greatly affected public perception of the Vietnam War. Morris is passionately anti-war, and much like Jack Crabb, it becomes abundantly clear upon listening to him speak that he doesn’t like what he sees. View an excellent documentary about John G. Morris called Get The Picture.

Career:

Daily Maroon (The Chicago Maroon), University of Chicago student newspaper, 1933-37

Pulse, University of Chicago student magazine, Editor, 1937-38

LIFE (magazine), Editorial Staff, 1939-46 : New York, Los Angeles, Washington, London, Chicago, Paris

Ladies’ Home Journal, Associate Editor (Pictures), 1946-52

Magnum News Service, Editor, 1952-63

The Washington Post, Assistant Managing Editor (Graphics), 1964-65

Time/Life Books, editor, 1966-67

The New York Times, Picture Editor, 1967-74; Editor, NYT Pictures, 1975-76

Quest/77-79, Contributing Editor, 1977-79

National Geographic, European Correspondent, 1983-89