If you were a Left-leaning college student in the 1960s there is a good chance that you had a copy of Ramparts magazine on the coffee table. From 1964-1969, under the leadership of executive editor Warren Hinckle, Ramparts was arguably the most important anti-war, counter-culture, general circulation magazine in the United States. Closely associated with the New Left political movement the magazine reached an ultimate circulation of 250,000 in 1968. That was a large number in those days, especially for an ostensibly underground publication frequently denigrated by its competitors in the mainstream media. Ramparts was so good at its craft that it became the ire of the CIA, which tried to censor the magazine and then shut it down, failing on both counts, not to mention breaking the law and its own charter prohibiting it from domestic spying.

Why was the CIA so rattled?

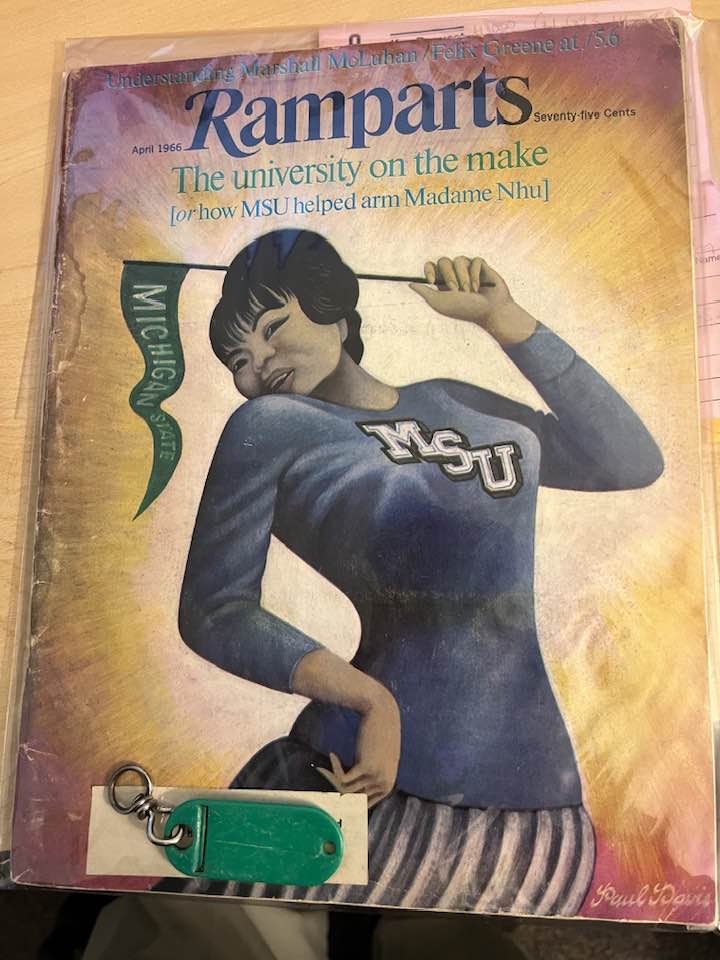

In the April 1966 edition Ramparts exposed a program the CIA was running clandestinely out of Michigan State University as part of the Michigan State University Vietnam Advisory Group (MSUG). Though there were some positive outcomes from MSUG the article revealed that the Agency had infiltrated it early on and was using it as a front for covert operations, including training and arming police interrogators in South Vietnam to spy on and harass dissidents in Saigon. Though not explicit in the record there were almost certainly some classes on torture methods in the curriculum. What we do know is that Diem’s forces had gained considerable expertise in using such brutal practices during the time period in question. Ramparts asked: “what the hell is a university doing buying guns, anyway?” It was one of the early sparks in what would erupt into open confrontations between students and their universities over support for the Vietnam War, most famously at Berkeley, Michigan, Columbia, Wisconsin, Ohio State and Kent State, among many others. Ramparts won the 1966 George Polk Award for Magazine Reporting for the article. The cover is a 60s classic (see below).

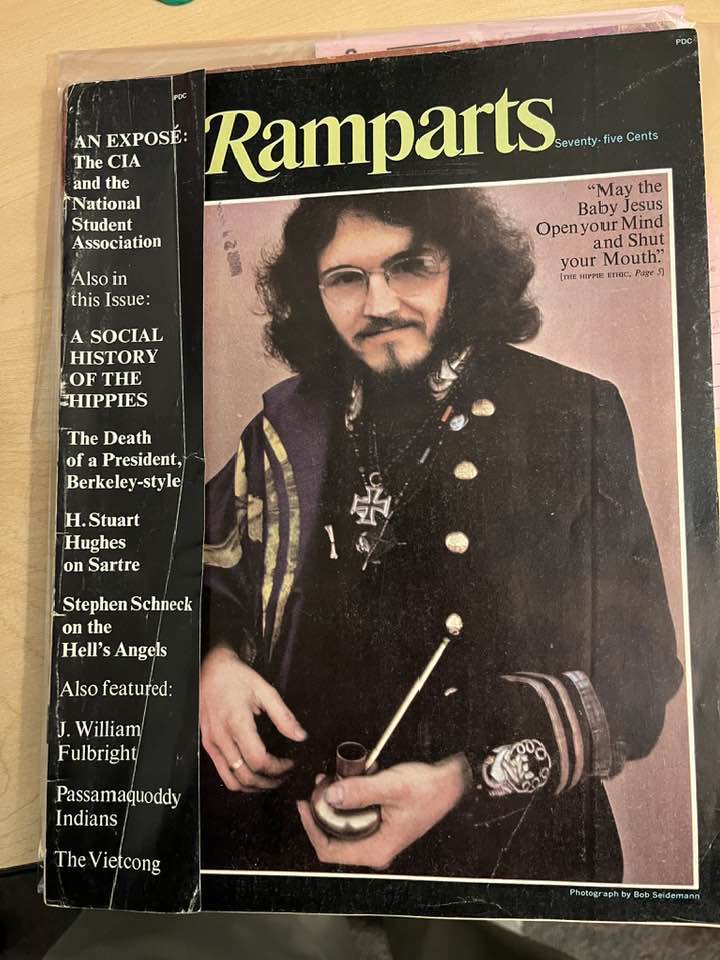

Then in March 1967 Ramparts created a national sensation by publishing an embarrassing expose of CIA secret funding of the National Student Association (NSA) which was the largest college student organization in America. A year earlier the New York Times ran a series of articles which began to uncover secret CIA funding of various fronts going back to the late 1940s, including arts organizations, political and cultural journals, radio stations, cultural foundations etc. That operation, known as the Congress For Cultural Freedom, aka the Mighty Wurlitzer within the CIA, was a primary weapon against Soviet influence in what is today known as the Cultural Cold War. But the Ramparts story went one step further by including the first acknowledgement of the program’s existence by a former CIA officer involved in the covert operations, Michael Wood, who had records, not just about the NSA, but other related fronts that the CIA had established. The upstart magazine had once again scooped the big players in the main stream media on one of the biggest stories of the time, pouring more gasoline on the fire on campuses nationwide.

For excellent treatments of this history see The Cultural Cold War by Frances Stonor Saunders and Cold Warriors by Duncan White.

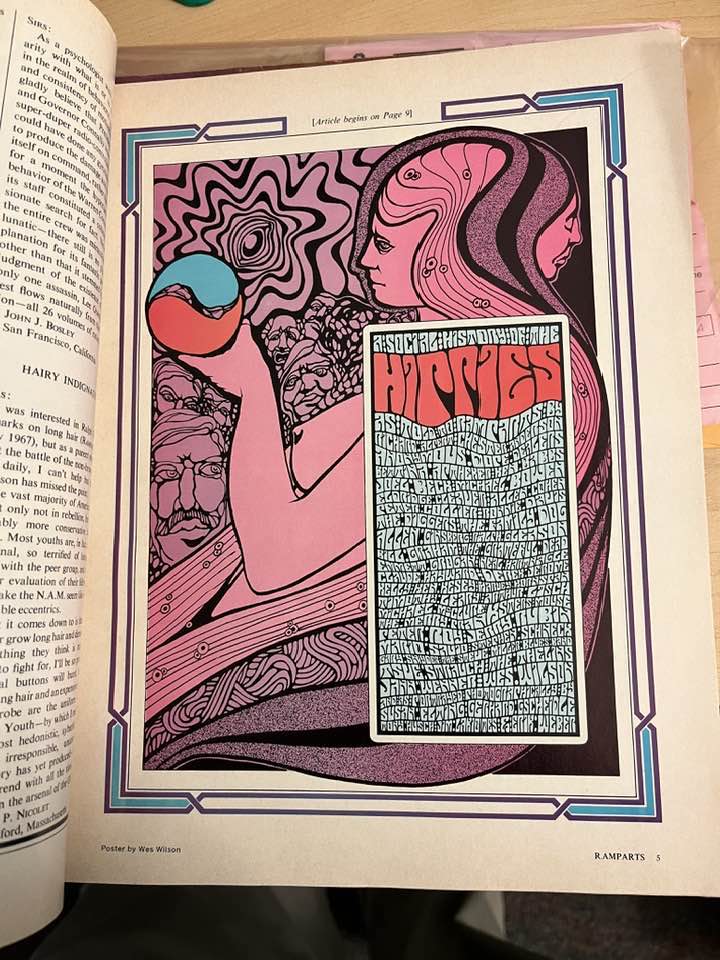

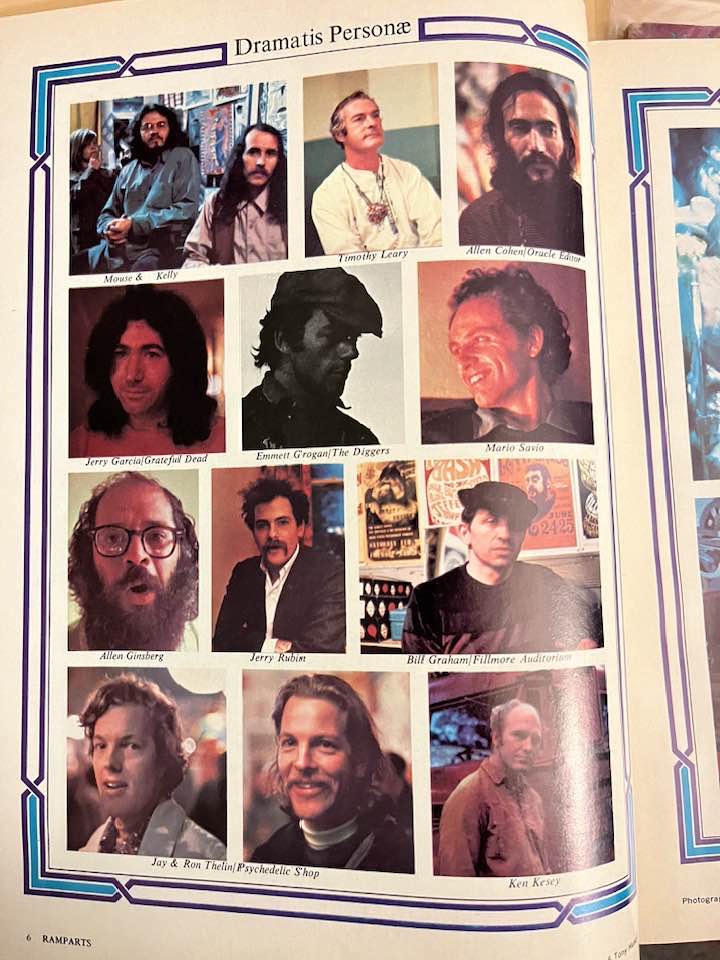

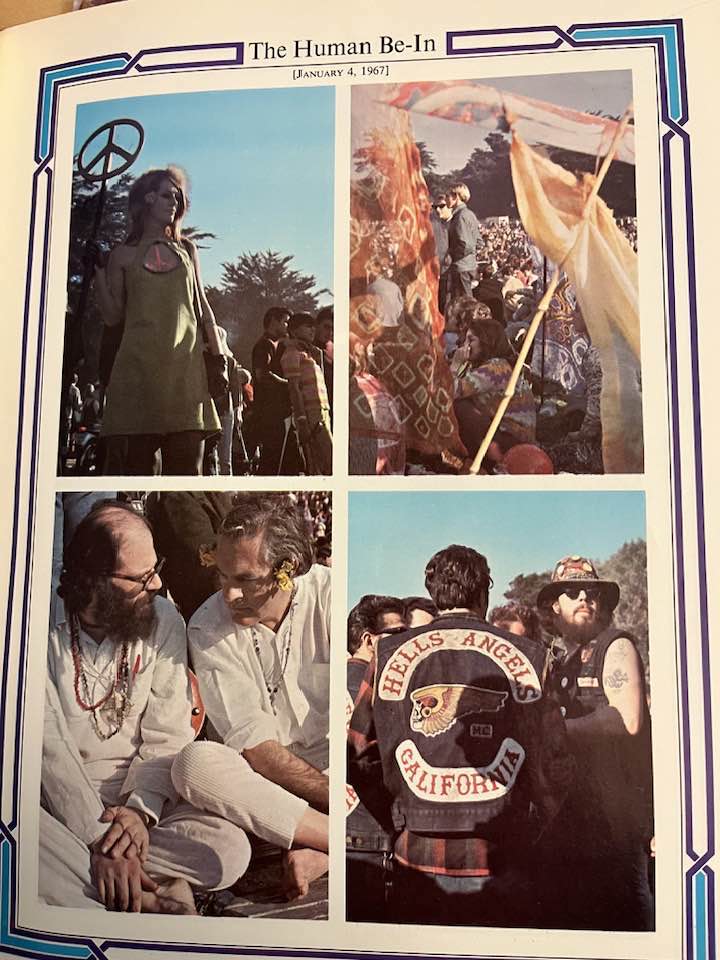

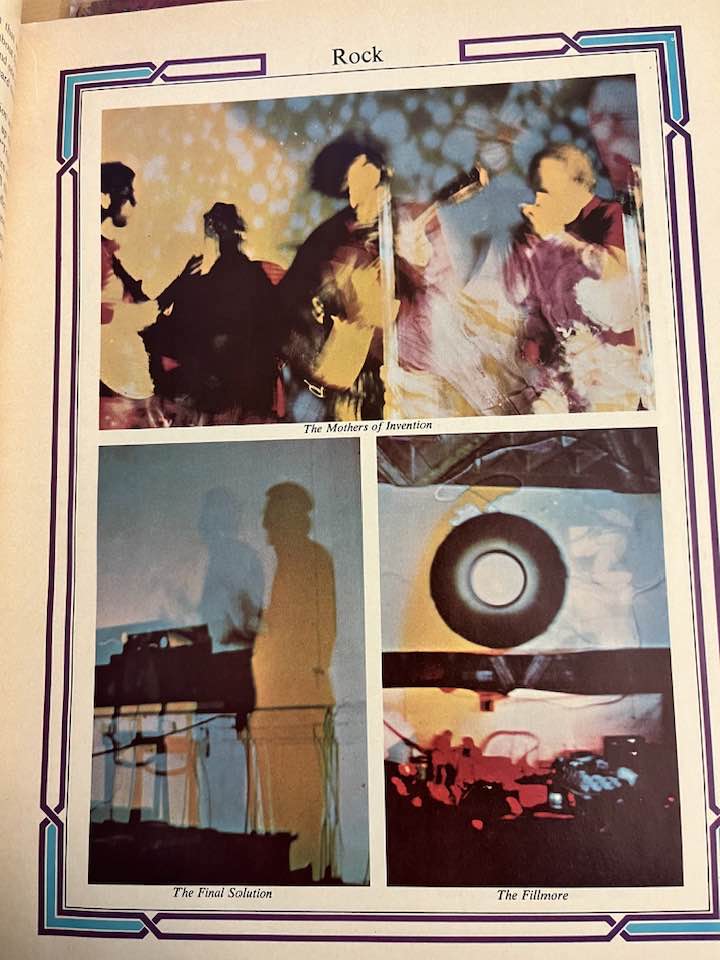

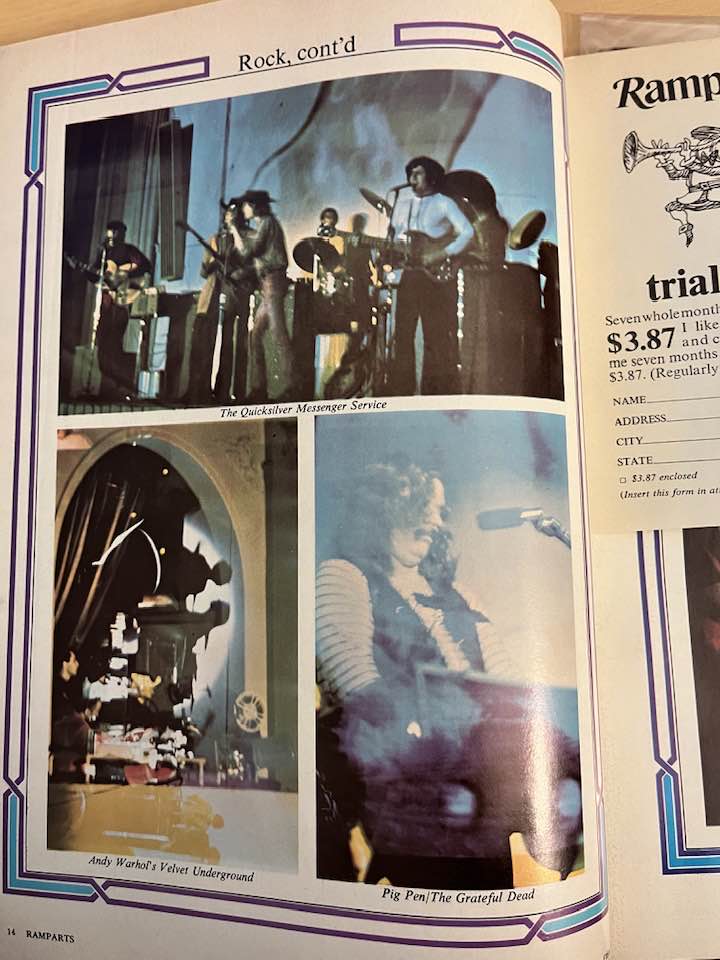

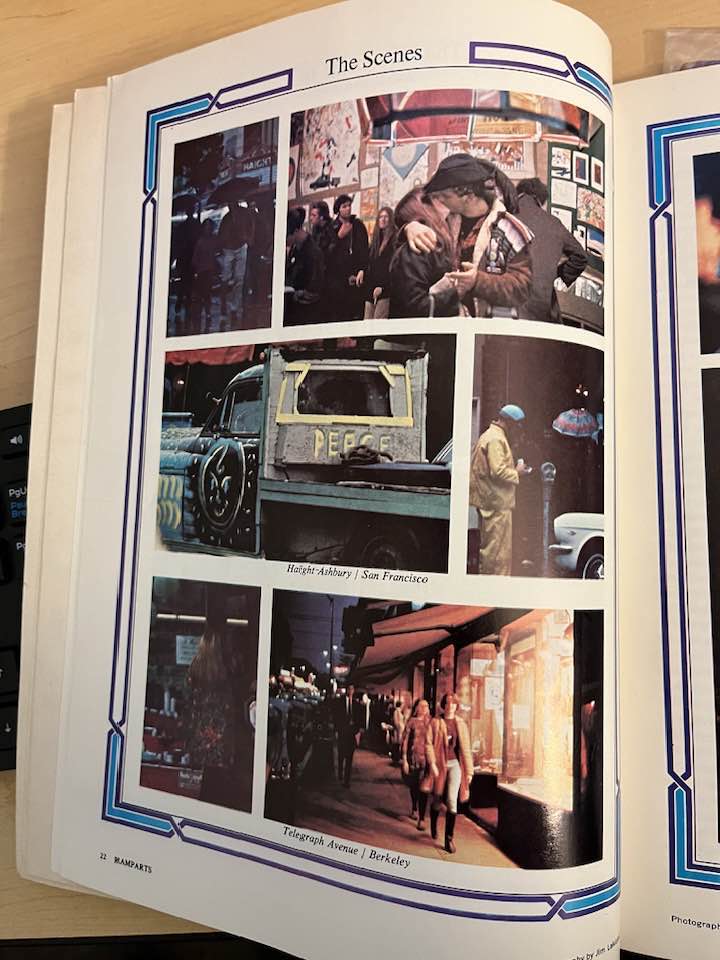

A side note about the March 1967 issue: Hinckle wrote the cover story, “A Social History of the Hippies.” Editorial differences over that story led contributing editor Ralph J. Gleason to resign in protest. Gleason and former Ramparts staffer Jann Wenner, then founded a new magazine, Rolling Stone, later that year.

Below are photos of these two landmark issues of Ramparts, they are two of the more influential magazine editions of any kind from the time period, helping to lay the foundation for the student radicalism that was to follow.

External Links:

Ramparts Editors on CIA Activities – KPIX TV (1967)

The University That Launched A CIA Front Operation in Vietnam – Politico (2018)

The Spy Who Funded Me: Revisiting the Congress for Cultural Freedom – LA Review of Books (2017)

NSA and the CIA – Ramparts Magazine, March 1967, pp. 29-39 text