The Panama Canal almost ended up in Nicaragua…

In 1902, after years of struggle and tragedy far from home, the French were grinding down in their calamitous Panama Canal effort. The overextended European power was anxious to cut its losses and hoped to entice the adventurous U.S. President, Theodore Roosevelt, into assuming ownership of the disastrous headache. The initial price offer was reportedly $100 million. Here in the States powerful business forces were pushing our government to blast our own shipping shortcut through Nicaragua and Congress was leaning toward the Nicaragua plan. The House had already voted in favor of building the canal there and it seemed a virtual shoo-in that the Senate would follow suit. The French reduced the price tag to $40 million out of desperation but the prospects for a successful sale appeared dim.

Then fate intervened. On May 8, 1902 Mount Pelee erupted on the island of Martinique, killing an estimated 29,000 people! It remains one of the deadliest volcanic eruptions in history. Even though Martinique is over 1,500 miles from Managua, it is in the Caribbean, and it was big news, so the question of volcanoes in the Nicaraguan canal zone resurfaced on Capitol Hill. The Nicaraguans sternly denied the presence of any active volcanoes and for the time being the vote looked safe.

According to author Stephen Kinzer, the French Panama Canal Company had hired an agent, William Cromwell, to lobby the U.S. Congress for the Panama option. Cromwell was about to leave town empty-handed when at the last minute a colleague showed him a recent Nicaraguan postage stamp. In an episode of unbelievable bad timing for the Nicaraguans, the stamp displayed a picture of the Momotombo volcano spewing lava and smoke. Seizing the moment, the lobbyist reportedly scoured the various Washington DC area stamp sellers and acquired copies to circulate to the senators. Accompanying the stamp was a note suggesting that the evidence proved that Nicaragua was no stranger to violent geological events and the Nicaraguans knew it. It was a Hail Mary, but the stamp ploy was successful. On June 28, 1902 The Senate voted for the Spooner Act authorizing the purchase of France’s Panama Canal assets. The Nicaraguan canal was dead. It was in an amazing turn of events that had devastating consequences for Nicaraguan people. (See Kinzer, Stephen – Overthrow: America’s Century of Regime Change From Hawaii to Iraq. Times Books, 2006)

The Fletcher Brothers’ Gold Mine…

When it looked like the canal would traverse Nicaragua, American officials and Nicaraguan President Jose Santos Zelaya enjoyed positive relations. After the deal fell through everything changed. Zelaya’s hostility toward foreign interests operating in and near his country grew. With time his rhetoric of economic nationalism proved to be his undoing. In 1906 he sent troops to neighboring Honduras, overthrowing a government that ruled at the behest of the United Fruit (Chiquita), Standard Fruit (Dole), and Cuyamel Fruit Companies.* He then tried to foment revolution in El Salvador for similar purposes. His efforts brought the area to the verge of international war, prompting intervention in Honduras by the United States to restore order, i.e., the fruit cartels.

Eventually the American interests decided enough was enough. According to Kinzer, American President William Taft closely followed the increasingly belligerent doings of Mr. Zelaya. When Zelaya threatened to cancel the lucrative La Luz y Los Angeles mining concession, and seize the mines held by the influential Fletcher Brothers of Pennsylvania, Taft’s Secretary of State Philander Knox used the pretext to go on the offensive. Kinzer describes the connection:

“the Philadelphia-based La Luz and Los Angeles Mining Company … held a lucrative gold mining concession in eastern Nicaragua. Besides his professional relationship with La Luz, Knox was politically and socially close to the Fletcher family of Philadelphia, which owned it. The Fletchers protected their company in an unusually effective way. Gilmore Fletcher managed it. His brother, Henry P.Fletcher, worked at the State Department, holding a series of influential positions and ultimately rising to undersecretary. Both detested Zelaya, especially after he began threatening, in 1908, to cancel the La Luz concession. Encouraged by the Fletcher brothers, Knox looked eagerly for a way to force Zelaya from power.”

Knox commenced a sabre rattling campaign in the press. He seized on several minor incidents in Nicaragua, one in which an American tobacco merchant was briefly jailed, to paint the Nicaraguan regime as brutal and oppressive. He sent diplomats to Nicaragua whom he knew to be strongly anti-Zelaya, and passed their lurid reports to friends in the press. Soon American newspapers were screaming that Zelaya had imposed a “reign of terror” in Nicaragua and had become “the menace of Central America.” As their sensationalist campaign reached a peak, President Taft gravely announced that the United States would no longer “tolerate and deal with such a medieval despot.”

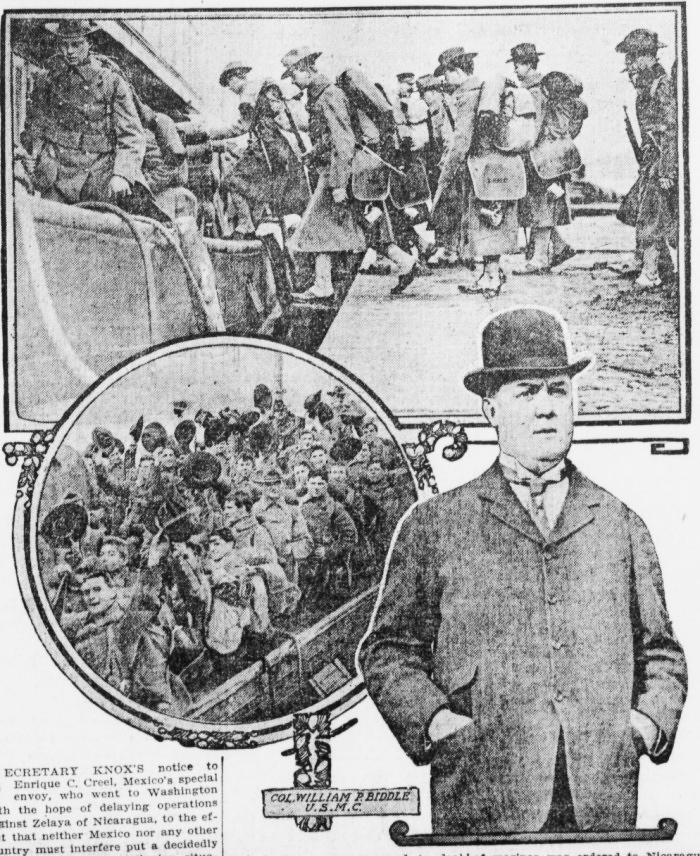

The handwriting was on the wall for the long-serving Nicaraguan president. In October 1909 an American proxy, General Juan Jose Estrada, declared himself president, igniting revolution in the country. When U.S. officials tried to persuade Costa Rica to invade Nicaragua in support of Estrada Costa Rican officials declined, stating that they considered the United States to be a more serious threat to Central American peace and harmony than Zelaya. Taft then ordered troops to Panama to further intimidate the besieged Zelaya. In December, the Nicaraguan president ordered the execution of two U.S. soldiers of fortune for fighting in Estrada’s rebellious army. Probably not the wisest course of action. The United States broke off diplomatic relations and the Marines landed in the country. Within two months Zelaya was forced to resign. He had ruled Nicaragua since 1893. Estrada later marched unopposed into Managua. The New York Times printed this when Estrada was sworn in: “On that day began the American rule of Nicaragua, political and economic.” (Kinzer – Overthrow)

A succession of conservative rulers went on supporting the U.S. military occupation that lasted until 1933. Meanwhile, the Fletcher Brothers continued to run their gold mines in Nicaragua.

The Sandino Insurrection…

After the fall of Zelaya the country endured years of humiliating subservience to foreign interests, with pliant rulers propped up by the U.S. Military. In the mid-1920s opposition increased, finally spilling over into civil war. By 1927 the war had been going on for three years and the fighting was becoming a real threat to U.S. interests. Rebels began to menace American companies, including the Fletcher owned mines. The American President, Calvin Coolidge, countered by sending more troops and proposing a solution which entailed United States oversight of a presidential election in 1928. In addition, funding was provided for the creation of a new national security force that was to be trained by the Marine Corps and nominally led by Nicaraguan soldiers, The Guardia Nacional de Nicaragua was born. (See U.S. Naval institute – Marines in Nicaragua, 1927-32)

The civil war was taking a heavy toll on Leftist forces. Many rebels had left the field, or had been killed. One refused to back down. In July 1927, with his legendary San Albino Manifesto, the revolutionary, Augusto “Cesar” Sandino, proclaimed his war of resistance against U.S. intervention. Over the next six years, his forces, the original Sandinistas, engaged in a military campaign that was a classic example of asymmetric guerrilla warfare. Once again, the Fletcher Brothers and their mines were at the center of events, and once again an American president sent troops, but this time the Marines could not save them.

According to a Herald Tribune report on April 23, 1928:

“The first report of the raid reached Mr. Fletcher, who is brother of Henry P. Fletcher, ambassador to Rome, on Saturday, April 21. It read: “On the 12th Sandino raided La Luz (name of the mine), taking all gold, money, merchandise, and animals. Also Marshall and all employees prisoners.”

“Mr. Fletcher immediately communicated with the State Department, asking that the Marines be sent to rescue the prisoners. Fletcher indicated that Sandino had returned to the mine following the raid on April 12 and was forcing the superintendent and his American assistants to operate the property, which he says produces about $30,000 worth of gold monthly.” (Herald Tribune April 23, 1928)

On May 7, 1928 Time magazine reported:

“Last week President James Gilmore Fletcher of the mining corporations and his co-owning brothers, G. Fred & D. Watson Fletcher, all of Manhattan, were irate. President Fletcher dashed to Washington to inform Secretary of State Frank Billings Kellogg that much was amiss in the valley of the purling Pis-Pis River. The Fletcher mines had been seized, he declared, by the forces of General Augusto Calderon Sandino, whom. U. S. Marines have been hunting vainly up and down Nicaragua for many a month.

To correspondents President Fletcher said bitterly: “My brothers and I are not in politics down there, and we have nothing to do with Wall Street. . . . From the meagre information I have the losses from looting our movable property may run to $100,000; but if the pipe line and mill plant have been destroyed the loss might run to $3,000,000 . . . and the owners would face ruin. … I guess this is what comes of investing one’s money in foreign countries.” (Time May 7, 1928)

On May 28, 1928 Time Magazine quoted from Sandino’s letter to Fletcher:

“I have the honor to inform you that on this day your mine has been reduced to ashes. . . . The losses which you have sustained in the aforementioned mine you may collect from the Government of the United States and Mr. Calvin Coolidge, who is truly responsible for the horrible and disastrous situation through which Nicaragua is passing at present.

“As long as the Government of the United States of North America does not order retirement of its pirates from our territory there will be no guarantee in this country for North Americans residing in Nicaragua.

“In the beginning I was confident that the people of North America would not be in accord with the abuses committed in Nicaragua by the Government of Mr. Calvin Coolidge, but I am now convinced that North Americans in general uphold the attitude of Coolidge in my country; and it is for this reason that all that is North American that falls into our hands assuredly will have come to its end.

“(Signed) Augusto Calderon Sandino, “(Seal)”

Such was a letter found last week amid the ruins of the two Nicaraguan gold mines owned by brothers of U. S. Ambassador to Italy Henry P. Fletcher which were recently gutted by Nicaraguan guerrillas with a loss of $2,000,000. (Time, May 28, 1928)

A year later, May 9, 1929 Time Magazine reported:

“President Coolidge sent 6,000 Marines to Nicaragua and their officers told them to “Get Sandino dead or alive!” In two years of furious guerrilla fighting no one ever “got” General Augusto Calderon Sandino, though at last this slender, sallow, wild-eyed patriot was driven from Nicaragua. Last week a roving correspondent found Sandino in Yucatan, the arid Mexican state which bulges like a sand blister out into the Gulf of Mexico.” (Time May 9, 1929)

After a devastating earthquake hit Managua, Sandino returned to Nicaragua in 1931 to continue the fight for liberation. His continued resistance was a key factor in the eventual removal of the Marines from Nicaragua in 1933, although deep military budget cuts brought on by the Great Depression in the U.S. were also critical.

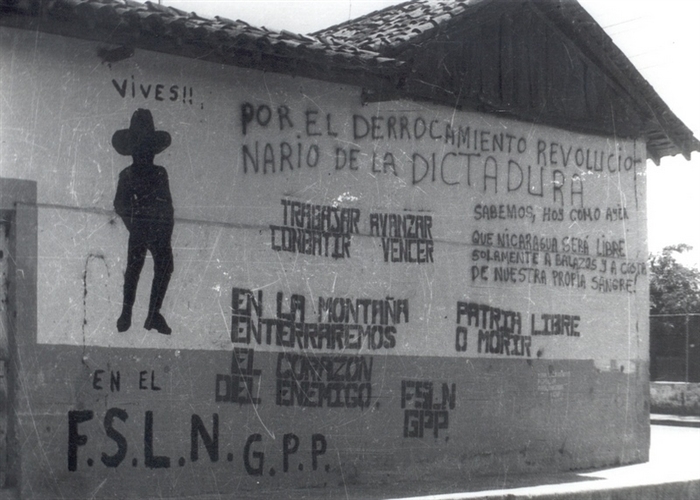

Sandino was never caught by the Marines, but he was eliminated nonetheless. While attending peace talks at the Presidential Palace in 1934 he was double-crossed by General Anastasio Somoza of the Guardia Nacional. The rebel leader’s murder was most likely carried out without the approval of the president, Juan Sacasa. The Guardia then forced Sacasa out of office and installed Somoza two years later. The Guardia Nacional de Nicaragua became Somoza’s personal police force and it kept the Somoza family dynasty in power for the following four decades. But in the end, in a textbook example of the phenomenon known as blowback, Augusto Sandino’s struggle, his defense of national self-determination, and his development of guerrilla warfare tactics, inspired the rise of Nicaragua’s Frente Sandinista de Liberacion Nacional (FSLN), the modern Sandinistas, who finally ended the right-wing Somoza family tyranny in 1979. What goes around comes around.

Epilogue...

Nicaragua’s failed dream of a canal linking its Atlantic and Pacific coasts turned out to be a costly nightmare. After the stamp episode and Zelaya’s subsequent overthrow by agents of the United States the country suffered through a series of banana wars and decades of tin-pot dictators and brutal Somoza family rule on behalf of American interests. The promise of the Sandinista revolution in 1979 was never realized, it did not arrest the poverty and strife brought on by years of political repression and economic instability. Today, its radical goals have largely faded into thermidor.

Panama’s reward for success on the other hand has been considerable. Around 14,000 ships transit the Panama canal each year, carrying 300m tons of cargo, earning the country about $2.5 billion in 2022. In 2022 the IMF ranked Panama 55th in the world in GDP per capita adjusted for relative purchasing power, Nicaragua did not make the top 100. (Panama Canal Traffic by Fiscal years)

*In 1904, the writer O. Henry coined the term “banana republic” to describe Honduras, inspired by his experiences there, where he had lived for six months.

Also of interest:

United States Intervention in Nicaragua, 1909-33

Congressional record, Senate April 1928

Remembering Sandino – Jacobin Magazine March 7, 2017

Jungle Journalism. Time Magazine March 26, 1928

The author interweaves the entire narrative with this class-warfare theme. Plentiful throughout are stories about pressure from below for political and economic reform vigorously countered by ruling elites. Over and over we read that the primary method for bolstering the bulwark against popular change was the manipulation of external threats to divert popular opinion. Nowadays we’ve heard the standard refrain all too many times, eerily similar to that of Livy– an enemy, real or perceived, threatens the national safety so an army must be raised. Senate (Patricians) can vote for war, but the Tribunes (Plebeians) can block the troop levy. Brinkmanship ensues, lines are drawn and scapegoating begins, political vacuums emerge and are filled, frequently by dictators, then more war. Dictators rise and fall, heroes are worshipped and human frailties frowned upon, gods are angered and placated with religious offerings, consuls and tribunes come and go. Through it all the populace is kept in constant fear of the barbarians just outside the gates. Rinse and repeat.

History reveals that the Plebeians have not fared well on average over the years in this environment. On the rare occasions when popular sentiment won the day the victors sometimes gained only the appearance of more power. Take the story of Servius for example. In it Livy explains that there was fairly broad suffrage among men in Rome, but that each vote did not carry the same weight from class to class. “The political reputation of Servius rests upon his organization of society according to a fixed scale of rank and fortune. He originated the census, a measure of the highest utility to a state destined, as Rome was, to future preeminence; for by means of its public service, in peace as well as in war, could thence forward be regularly organized on the basis of property; every man’s contribution could be in proportion to his means.” Livy states that “this had the effect of giving every man nominally a vote, while leaving all power actually in the hands of the Knights and the First Class.” (Livy, 1.44) Hence a narrowing of the field upon which the struggle for power is contested to a small number of privileged property owners.

Now think about how the US Congress is stacked against the popular will. By the time each Congress comes to order for the first time we the people have already surrendered a significant portion of our popular will by allowing ourselves to be winnowed down to 535 representatives (plus DC’s 3 electoral votes), some of whom stay on for decades. This narrowing of the target range to a manageable size creates a distinct advantage for influence peddlers (lobbyists and their benefactors). Then we double down by giving the less representative Senate the filibuster, thereby allowing a determined minority to kill bills that might emerge from the popular passions of the more representative House. The founding fathers did this by design to offset the tyranny of the majority. This is one of the famous checks and balances, and to be clear, by itself it is a strong philosophical concept and a serious requirement in a democracy. How else to offset the rule of the mob? In an oligarchy unfortunately it becomes a device to lock-in the desires of the ruling class. So, in the Senate, Wyoming has just as much power as California. Two senators each. Again the targets are narrowed even further for those fortunate enough to be allowed on the shooting range. Add a pinch of Citizen’s United and a dash of Gerrymandering and just as in Livy’s day there is broad suffrage, but most power actually resides in the hands of the Knights and the First Class. In that environment it is easy to see how the hopes and aspirations of the many can easily be hamstrung by the wishes of the few. Any wonder that it took one hundred years after the Civil War, and numerous failed attempts, to pass a civil rights act?

Livy writes in the preface: “The study of history is the best medicine for a sick mind; for in history you have a record of the infinite variety of human experience plainly set out for all to see: and in that record you can find for yourself and your country both examples and warnings: fine things to take as models, base things, rotten through and through, to avoid.”

The class struggle still exists, and it is still rotten. For the Plebeians hope is the dope their masters keep pushing, but it’s a weak dose, just enough to keep ’em strung out. The Patricians meanwhile continue to sit high on the hog. The history is there for all to see, but the power elite owns powerful tools to blind people from seeing it, and hence learning lessons from it. They keep a nice clean the sheet of the collective memory. When is the last time you saw a history of American labor on the TV? We get barraged with content on the history of war, and capitalism, and politicians, and celebrity, but you will be hard-pressed to find anything on the struggle for unions, equal rights and fair wages and better working conditions. Several years ago I visited the Newseum in Washington, which was advertised as the national museum on the history of the American media, dedicated to news and journalism that promoted free expression and the First Amendment. I found precious little material on working class movements, strikes or industrial and corporate malfeasance. How much of this information were you taught in school? How much is in the textbooks? Yet most of us spend a large portion of our waking lives laboring. I imagine you will hear plenty about Chinese balloons today though. Not much has changed in the 2700 years since Livy’s tales. RF