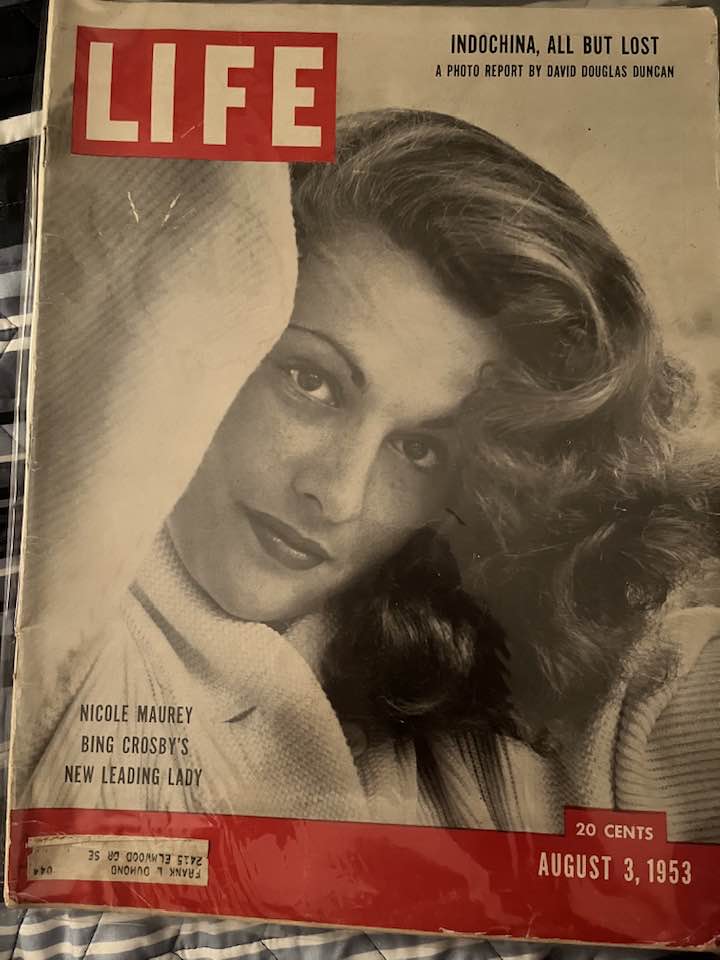

Life Magazine August 3, 1953 – Pessimism Sets In

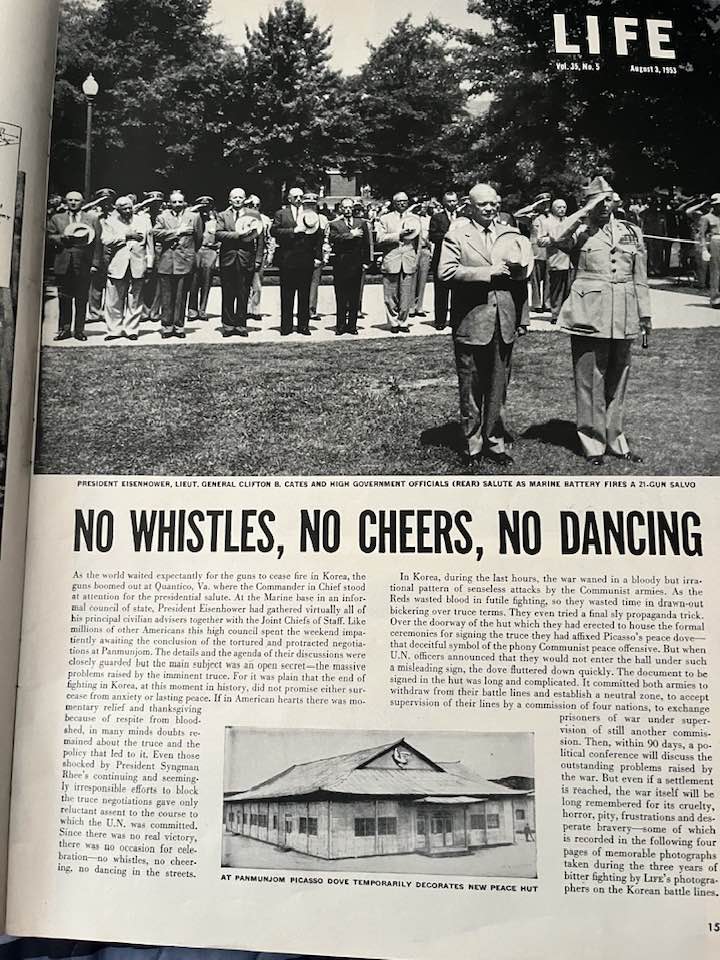

This issue is notable for several reasons. First, there is an article covering the ceasefire agreement ending formal fighting in the Korean War. Entitled “No Whistles, No Cheers, No Dancing” it is less than enthusiastic, not surprising considering Henry Luce’s antipathy toward the Chinese Communists. The French were also less than enthusiastic about the agreement, since it freed up the Chinese to focus on supporting Ho Chi Minh’s forces in the ongoing Indochina War.

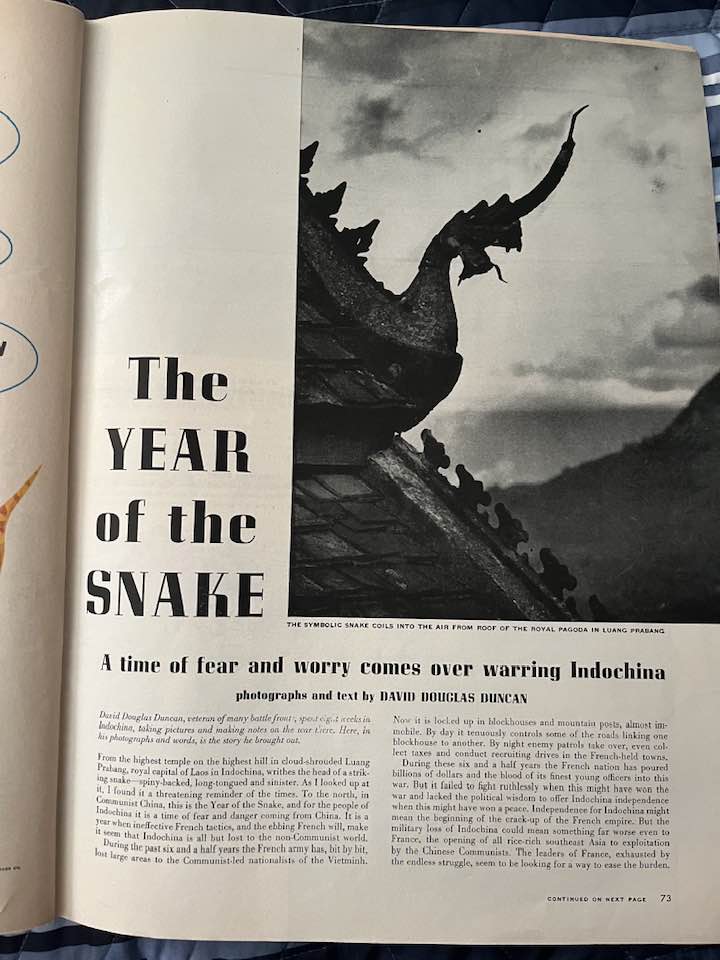

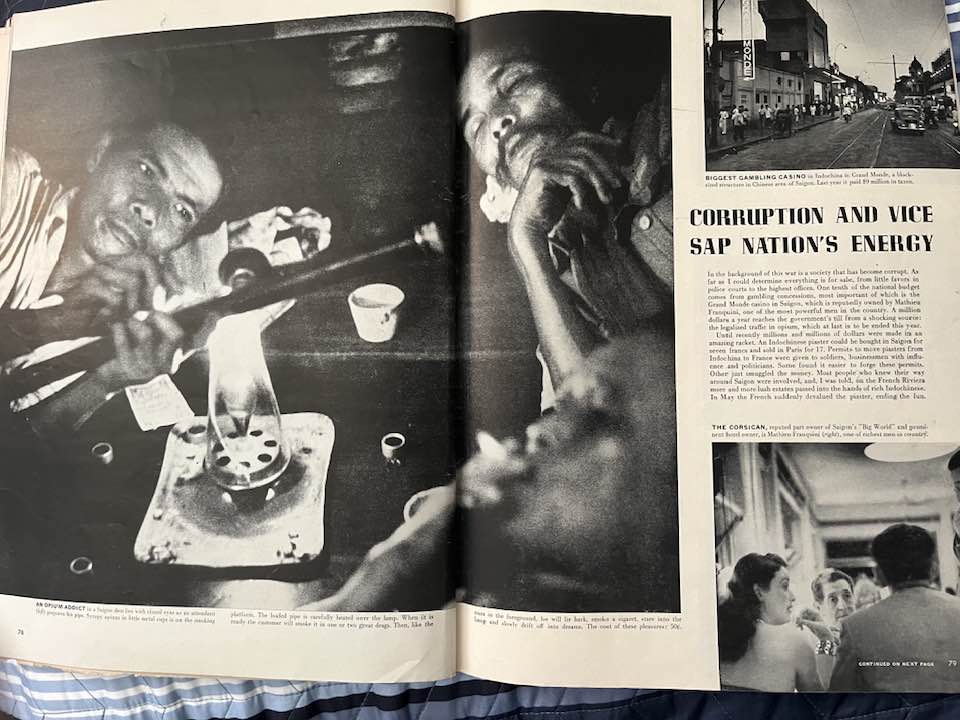

Second, we are introduced for the first time in the Vietnam context to the great combat photographer David Douglas Duncan, from whom we will see more during the American phase of the war. The photos captioned “Corruption and Vice Sap Nation’s Energy” convey the effects of the opium trade in Saigon. We get a rare glimpse of the Grand Monde Casino and the French underworld boss Mathieu Franchini, the Corsican, who controlled most of Saigon’s opium exports to Marseille. (see Bodard, Lucien, The Quicksand War: Prelude to Vietnam. Faber and Faber Limited, London, 1967. And, McCoy, Alfred. The Politics of Heroin in Southeast Asia. Harper and Row, New York, 1972.)

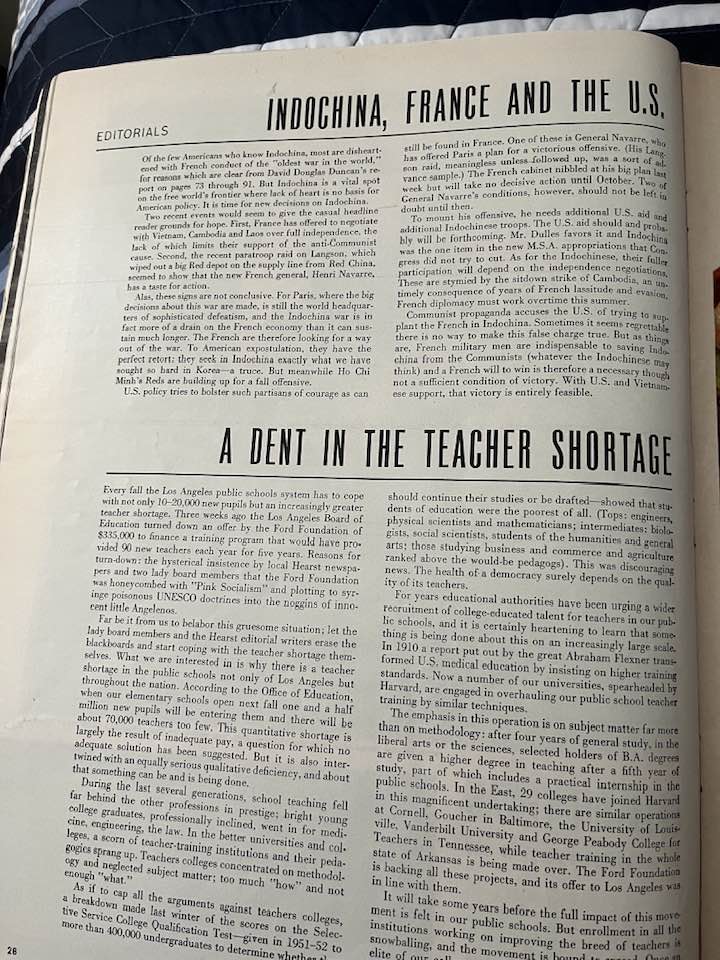

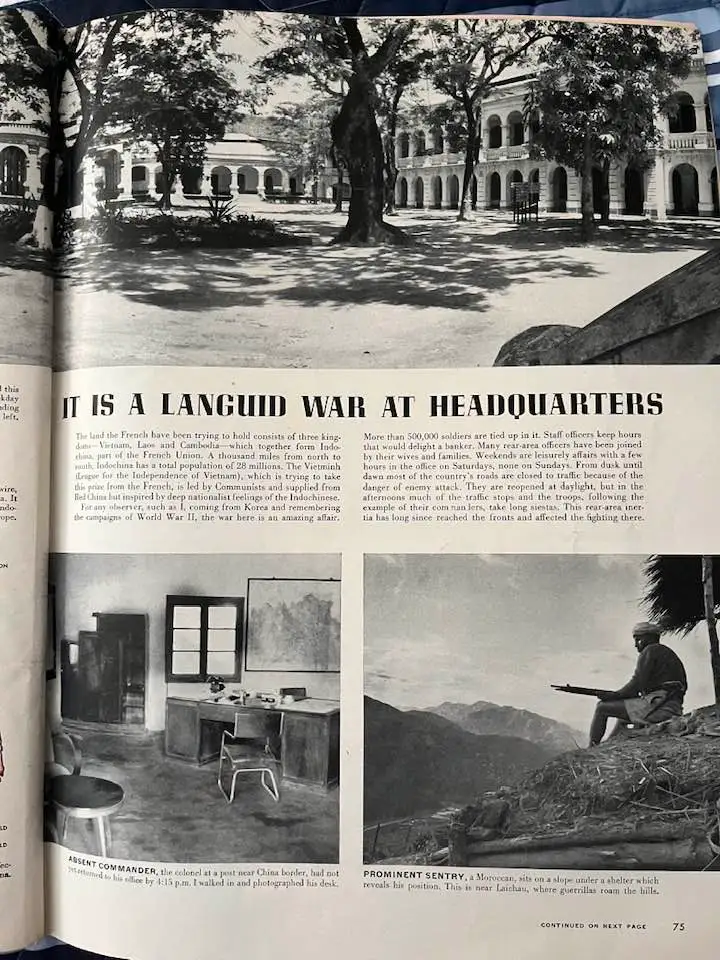

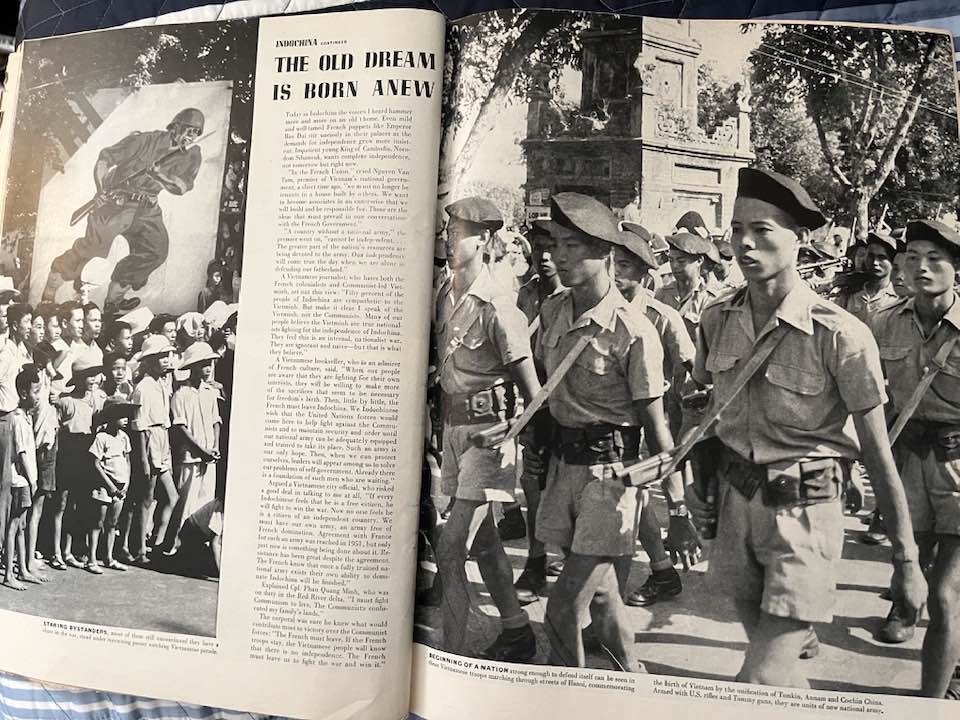

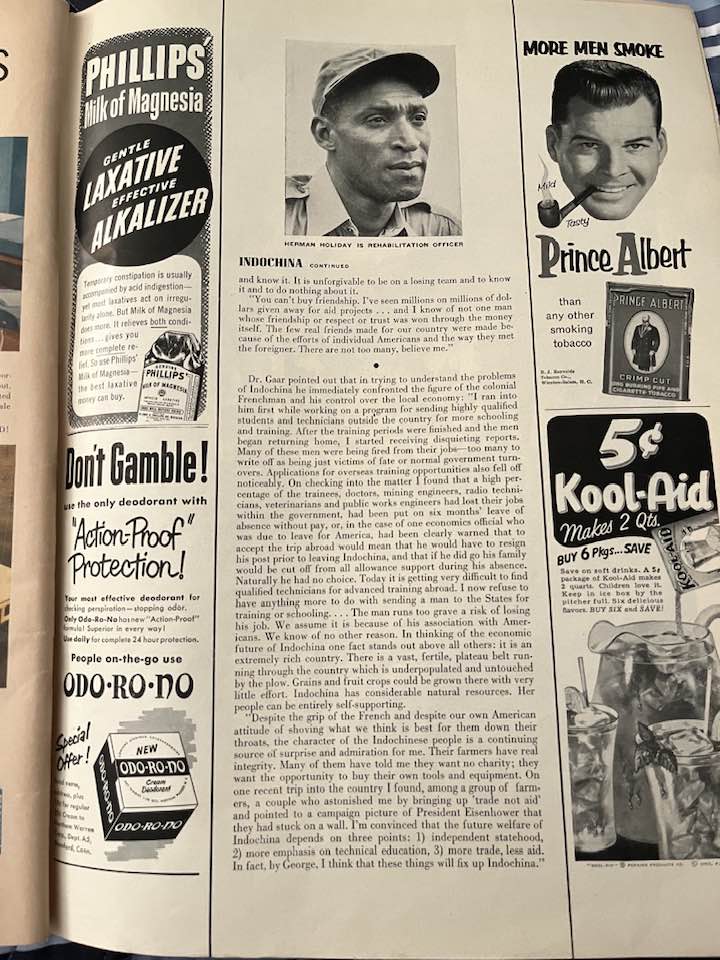

Last, with the title “Indochina All But Lost” featured on the cover, the first time that the war is mentioned on a cover, a turn toward pessimism about the ultimate outcome is apparent. The editorial on page 28 titled Indochina, France and the U.S. (shown below) posits that “Americans who know Indochina” are disheartened with France’s conduct of the war, calling Paris “the world headquarters of sophisticated defeatism,” and that it is time for new decisions on Indochina.*

This was an abrupt departure from the hopeful tone of previous Life reporting on the Indochina War. Just two years earlier the novelist Graham Greene had visited Vietnam, sent by Luce as a correspondent for Life. In the July 30, 1951 issue Greene reported on the war in Malaya, known as the Malayan Emergency. He crossed into the Tonkin region of Indochina on that trip. He ends his article with a comparison between the two insurgencies, both featuring colonial armies fighting local Communists. Greene applauds the performance of the Vietnamese Catholic infused forces that were helping the French while he denigrates the Malayan armed police fighting alongside the British, a hasty judgement that may have been clouded by his overt Catholicism. Yet, with more time spent in Vietnam, after gaining a better understanding of the situation, history and players, his confidence appears to have waned. A subsequent report, while not overly critical of the French forces, was not enthusiastic about their chances of prevailing either. Luce censored the article, and no other American publishers would run it. The piece ended up in the French magazine, Paris Match, for which Greene had become a correspondent. What he saw on that assignment, and future trips for Paris Match, provided the foundation for his masterpiece “The Quiet American,” considered to be one the greatest novels of the Cold War period. (see Greene, Graham, Indochina: France’s Crown of Thorns, Paris Match, July 12, 1952. And, Greene, Graham, Reflections, ed. Adamson, Judith, Reinhardt, New York, 1990.)

* The editors mention the arrival of General Henri Navarre and his proposed plan for a victorious offensive as a hopeful development. They urge Paris to accept the plan, stating that with “Vietnamese and American assistance victory is entirely feasible.” This so-called victorious offensive turned out to be Operation Castor, which ended with the Battle of Dien Bien Phu.

Related Articles:

All Propagated with the Best Intentions”: Greene, the U.S. and Indochina 1951-55

Graham Greene’s Prescient War-Reporting from Vietnam Predicted How Badly It Would Go

How Graham Greene’s Novel About American Policy in Vietnam Was Subverted by Hollywood