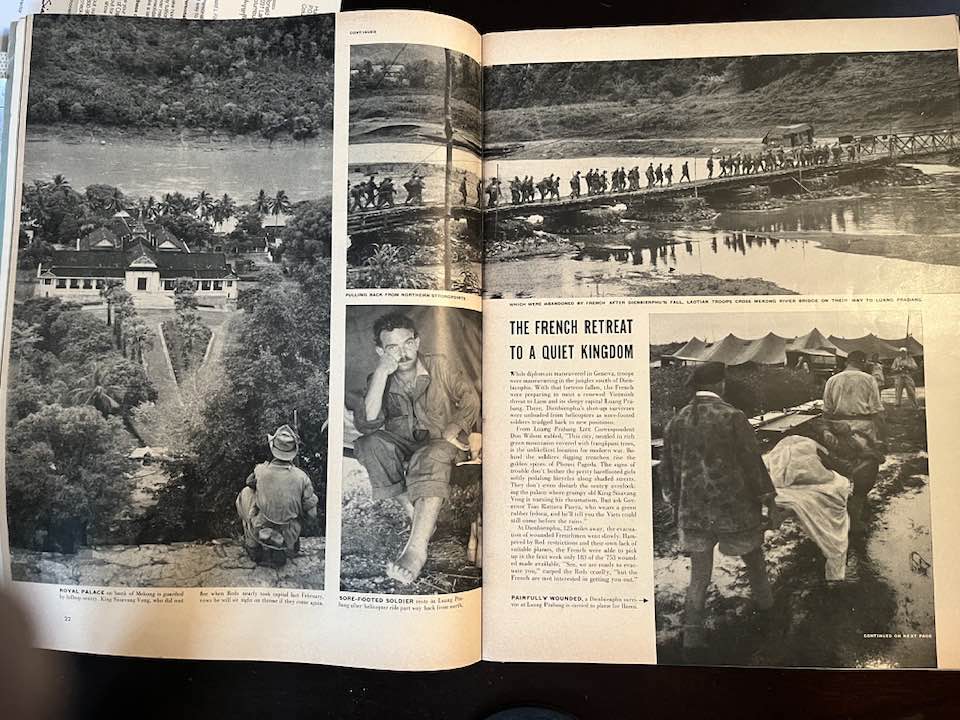

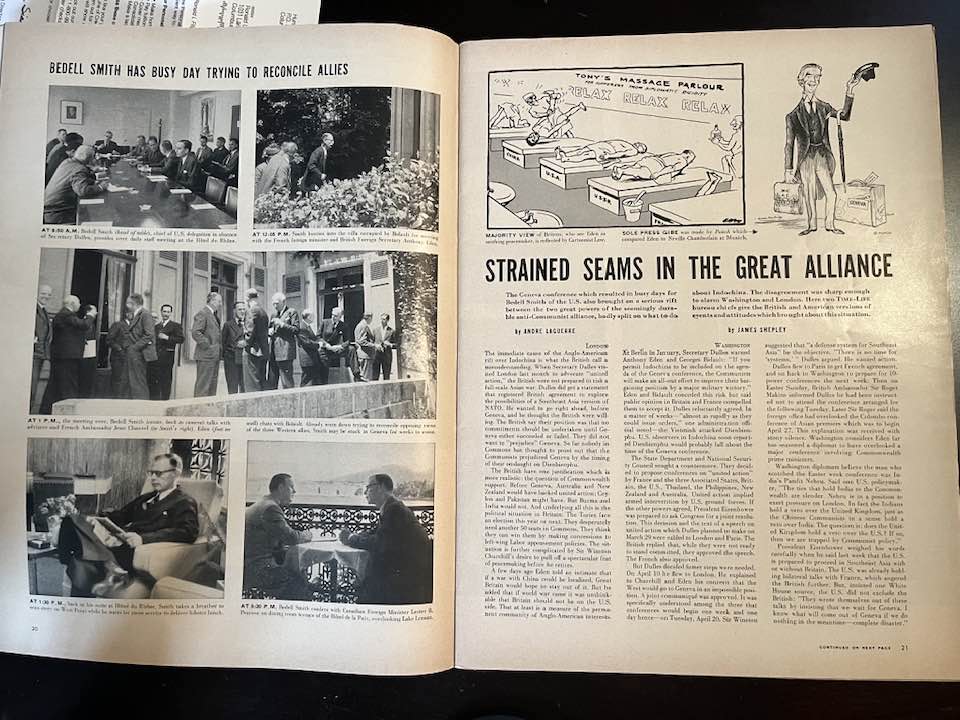

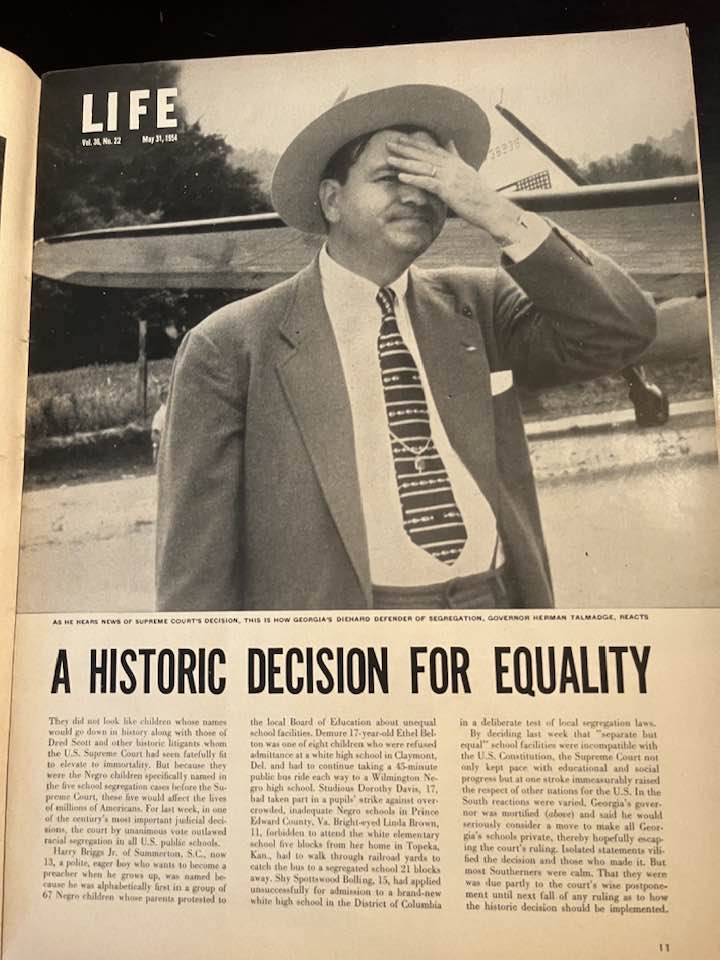

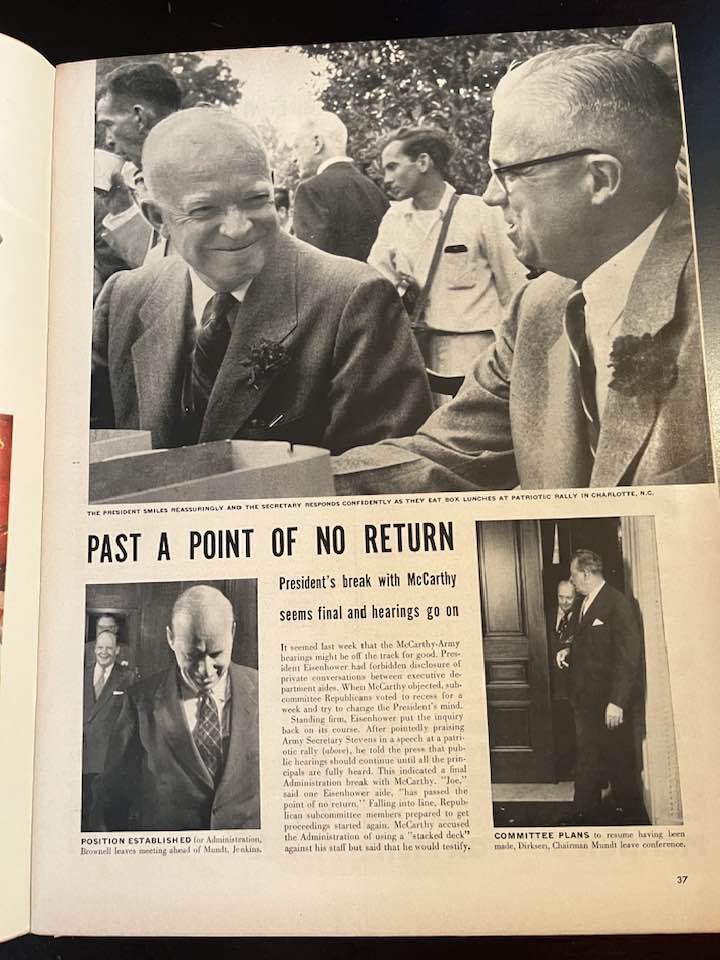

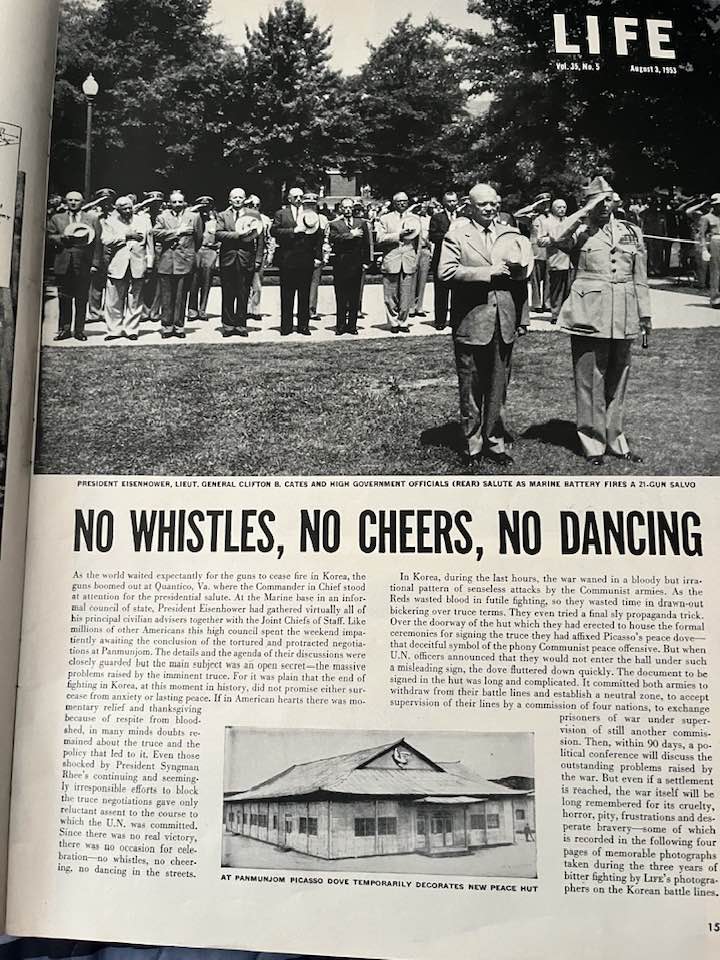

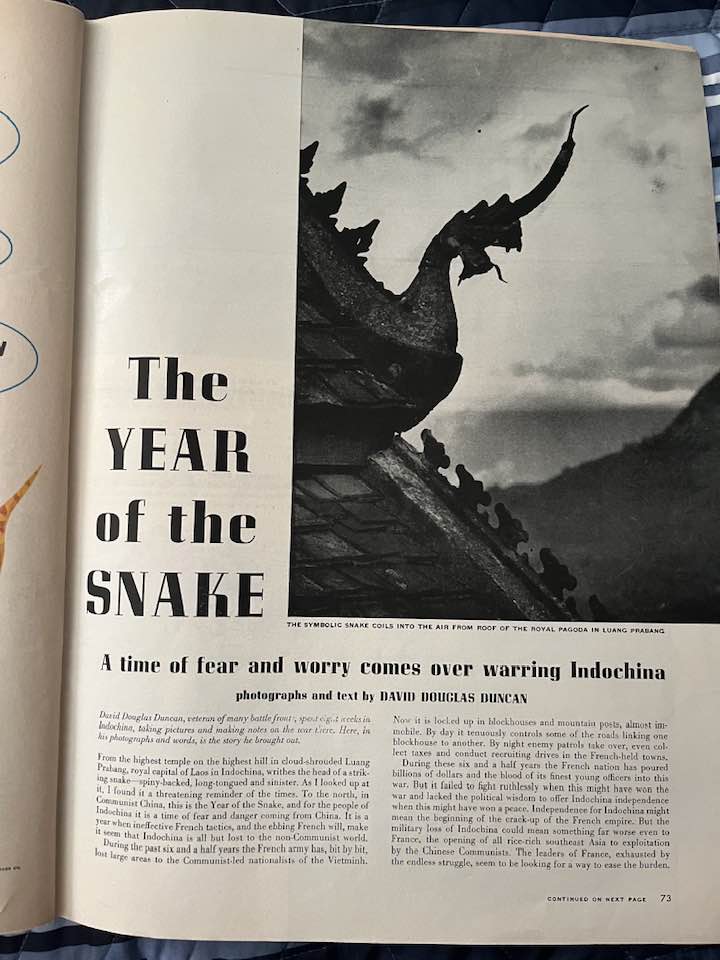

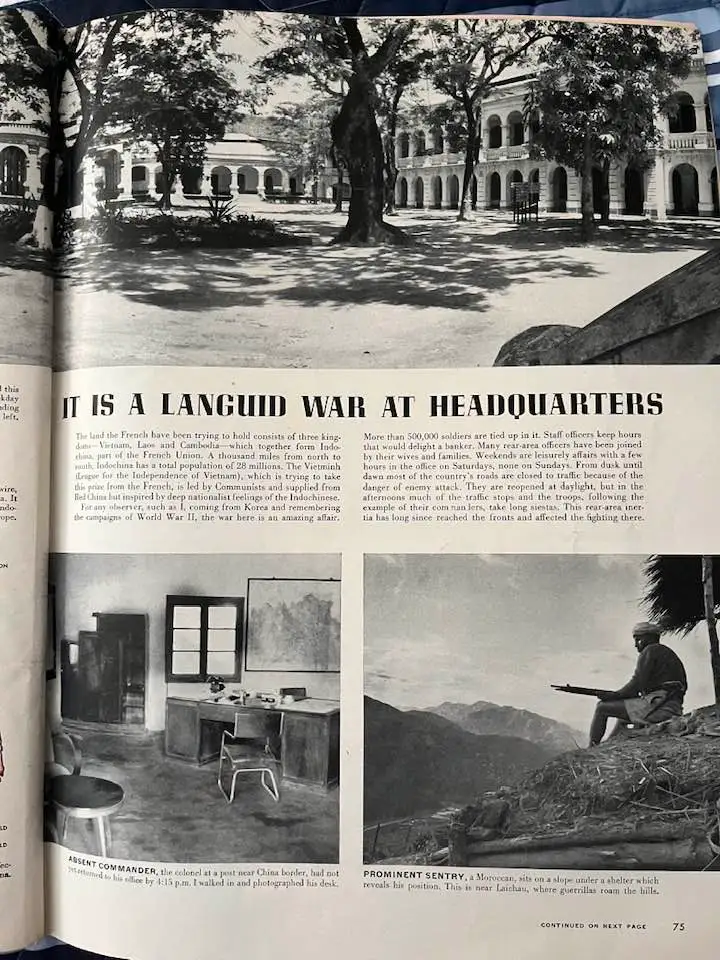

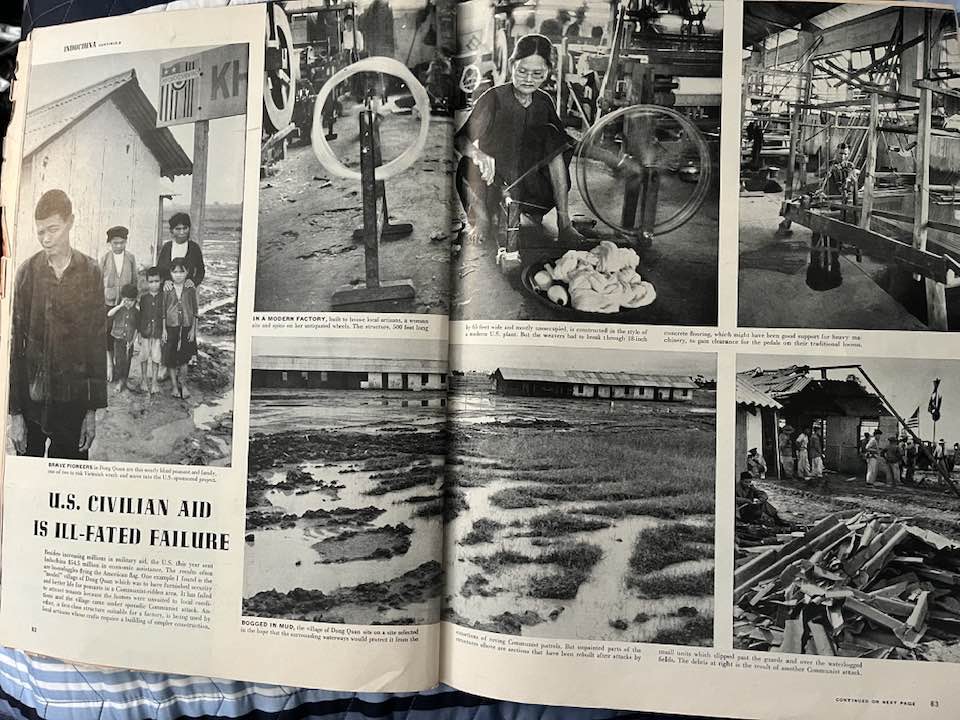

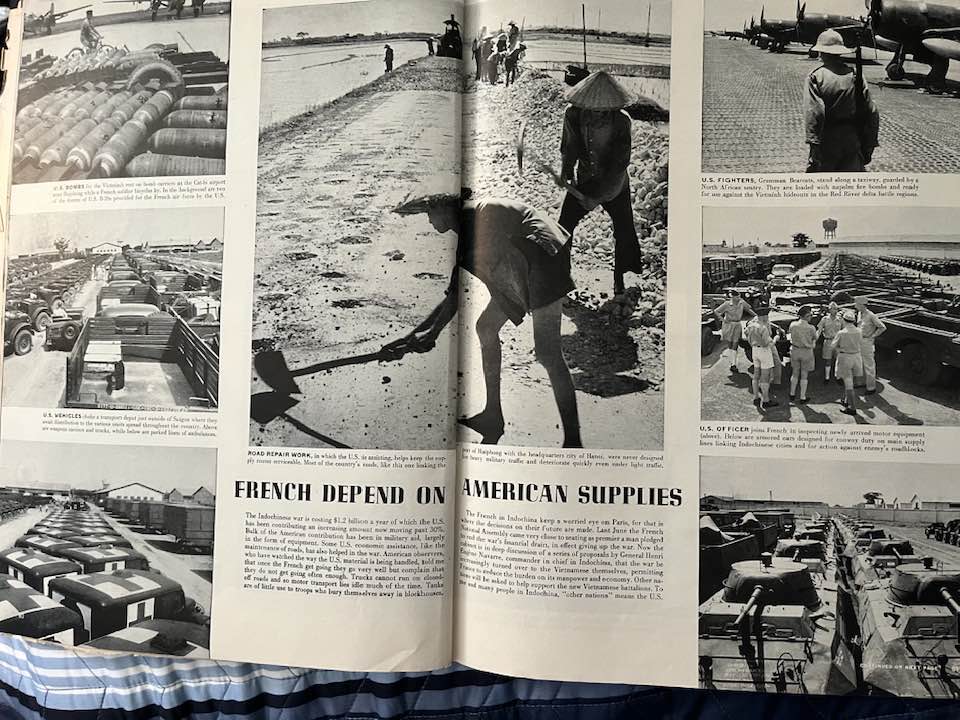

Life Magazine May 31, 1954. You’d be hard pressed to find a month in mid-century American history with more consequential events for the following decades than this one, and Life magazine was there. An article covers the French loss and retreat at the Battle of Dien Bien Phu and the subsequent Geneva Conference that led to the partition of Vietnam at the 17th Parallel. Another reports on the Brown vs Board of Education decision, which signaled the beginning of the Civil Rights era. We also learn that the Army hearings that finally brought down Joe McCarthy were under way.

Senator Joseph McCarthy (R-Wisconsin) had been riding high for several years on his claim that the Democrats were soft on, or in league with, communism and hence the government had become riddled with communists, especially the State Department. The ensuing anti-communist hysteria, known as the “Red Scare,” had brought the Republicans back to power for the first time since before the Great Depression. One tactic of red-baiting that the GOP exploited to great advantage was the claim that Truman and the Democrats had “lost” China by allowing Mao to come to power in the Chinese Revolution in 1949. The crusade known as McCarthyism caused enormous political damage and ruined many careers and lives. But now Tail Gunner Joe’s star was fading. His harsh right-wing grandstanding, much of it unsubstantiated, and his drunken antics had become a liability. Eisenhower had turned on him. Henry Luce on the other hand would remain a major espouser of the lost China accusation for years to come (Chiang Kai-Shek was his close friend). His publications would exert powerful domestic pressure on Eisenhower, who decided to involve the country in a series of Asian misadventures in Indonesia, Laos, and Vietnam.

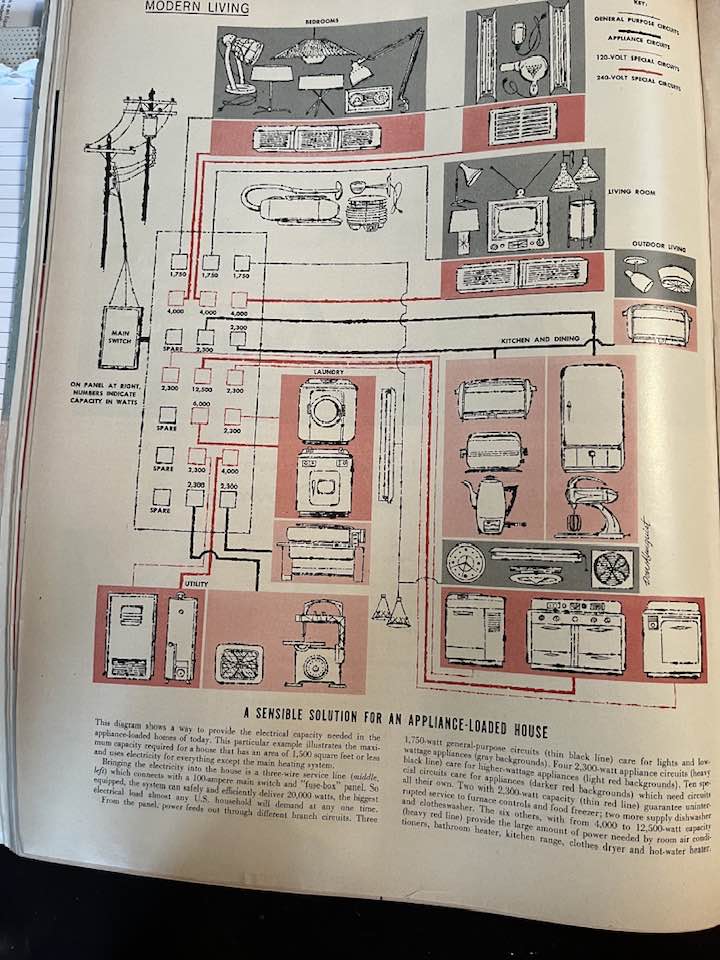

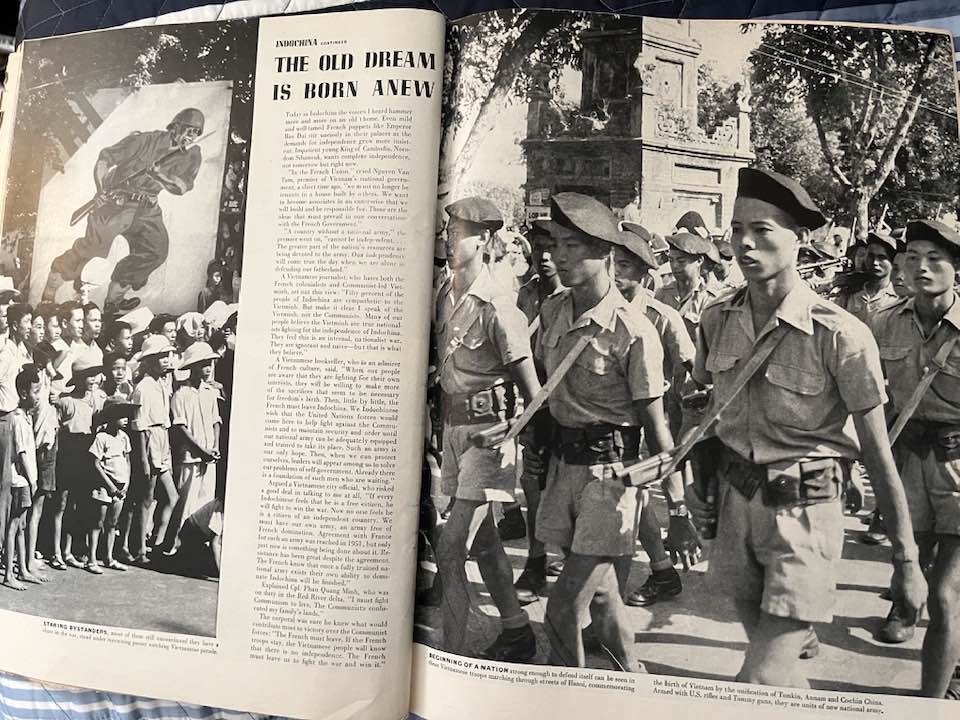

These threads would merge a decade later as the U.S. sent a massive military deployment to Vietnam, many of whom were black, brown and American Indian, in an ill-fated attempt to roll-back the communist threat officially labeled as the “domino theory,” a phrase coined in 1954 by Eisenhower in justifying initial military support for the American installed government in South Vietnam. This issue truly contains the seeds of the sixties. There is also an article on the science of flying saucers and an electrical schematic for “A Sensible Solution For An Appliance-Loaded House.”